The Swiss Learner Corpus SWIKO

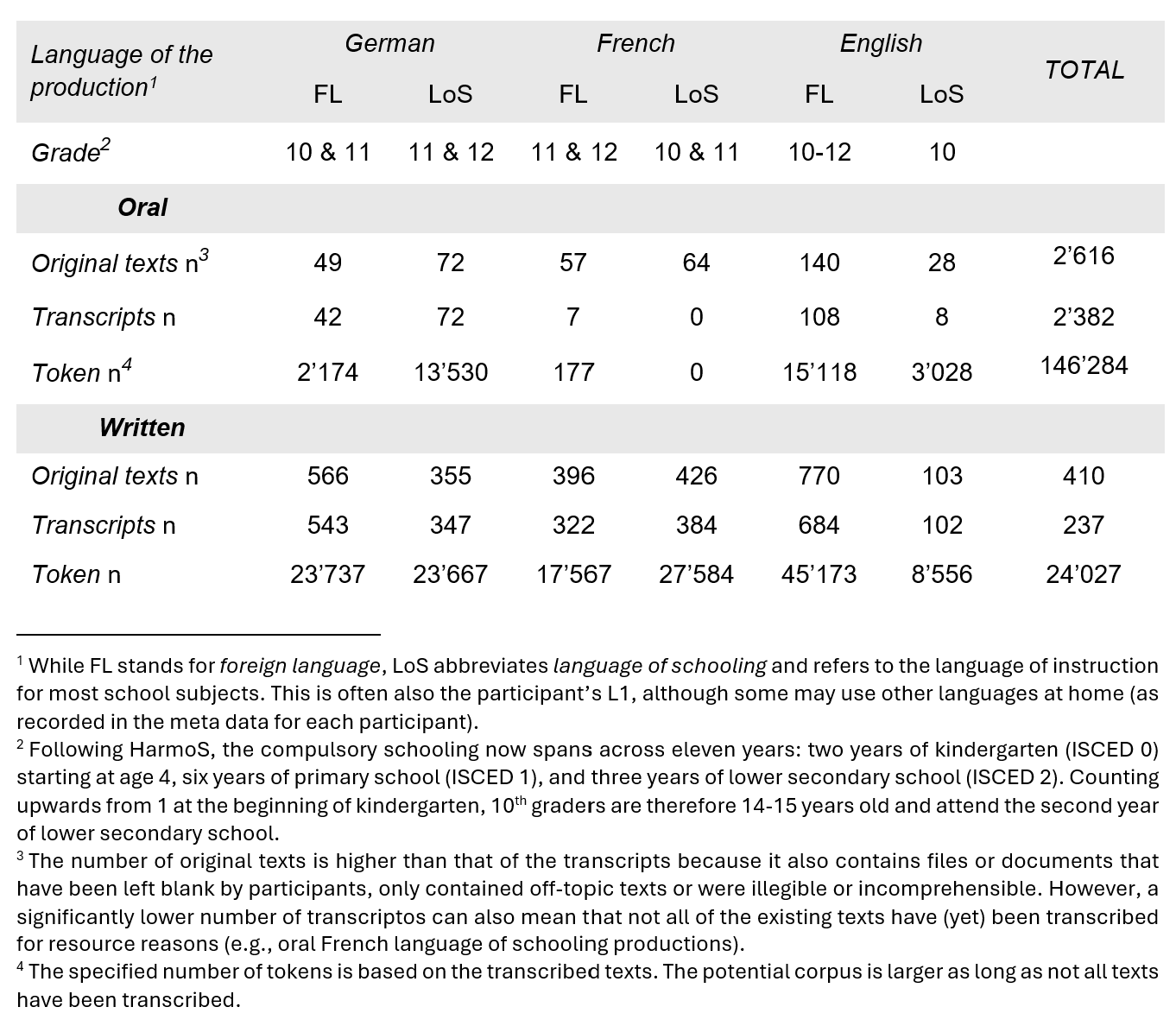

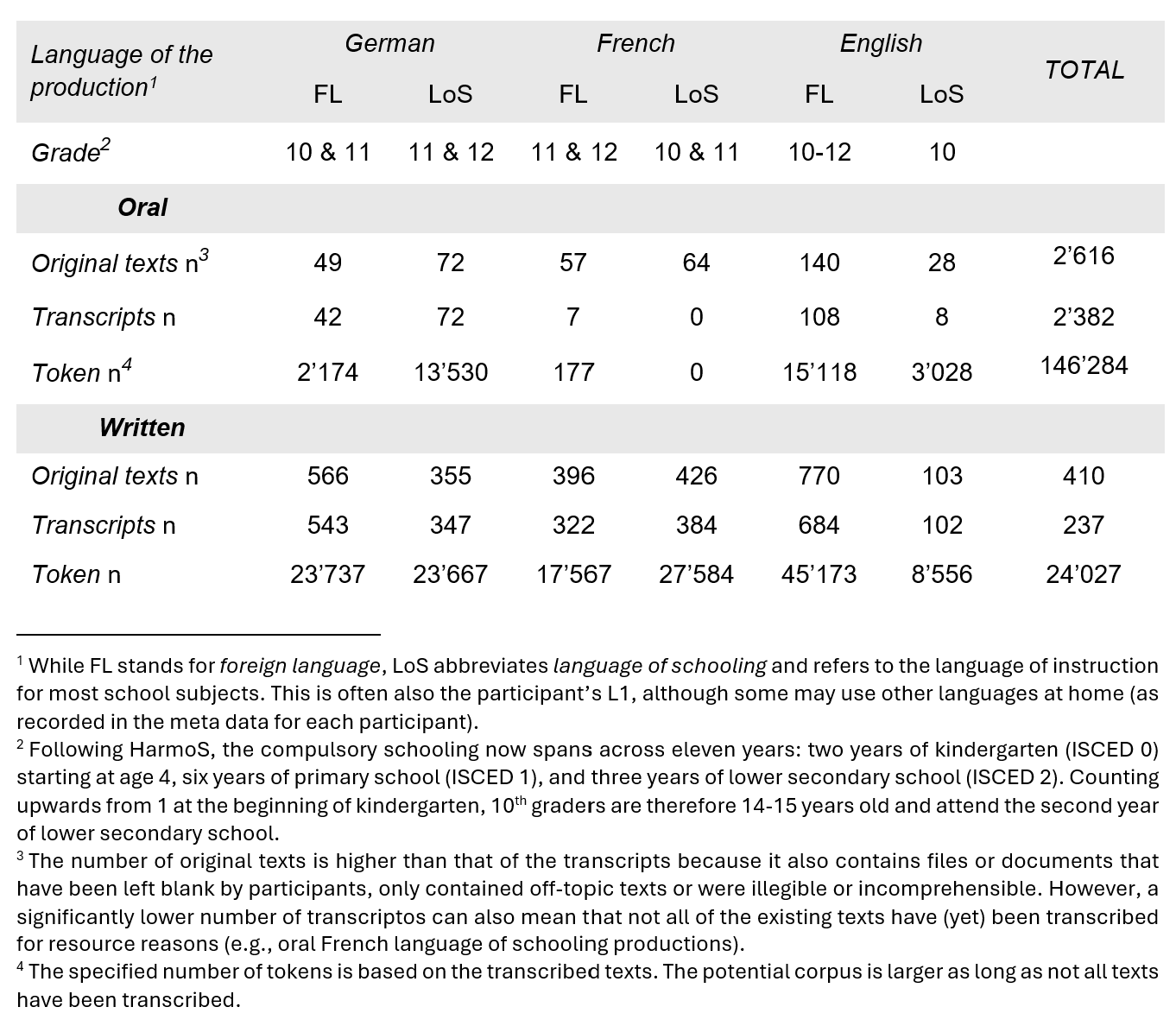

The Swiss Learner Corpus SWIKO is compiled as part of the SWIKO and WETLAND research projects at the Institute of Multilingualism in Fribourg (CH). Currently, the corpus contains over 2600 annotated texts containing more than 170'000 tokens. These are based on oral and written productions by Swiss lower secondary school students in German, French, and English, both as their language of schooling and foreign languages.

This website provides information about the project, particularly regarding data collection and processing, derived from a number of project internal documents. Additionally, some use cases for the classroom, material design and research are suggested.

SWIKO's online corpus databank is openly available and access to our partner project's datasets can be obtain upon registration.

Corpus design

Use scenarios

Introduction [Back]

Context and aims

SWIKO is a multilingual parallel corpus, developed during two research project phases at the Institute of Multilingualism in Fribourg, CH . The project investigates selected areas of linguistic competence among Swiss (lower) secondary school language learners. The idea for the project stems from a shift in instructed foreign language learning: Around the turn of the century, instruction became competence-based, as well as action, content, and task-oriented (Council of Europe, 2001). In Switzerland, this coincided with the HarmoS project, wherein the foreign language instruction in public schools was unified across most cantons (e.g., Lehrplan 21, D-EDK, 2023; or New World, Arnet-Clark et al., 2013). As such, two foreign languages became mandatory in primary school: the first one starting in Grade 5, the second in Grade 7, with one national language plus English. For example, in French speaking Switzerland, students start learning German at age 8 and English at age 10. At the end of mandatory schooling – in grade 11 at the age of 15 - students are expected to reach level A2.2 overall, and level A2.1 in writing. These thresholds apply to both foreign languages.

What we know so far from a first national monitoring (ÜGK, 2019) and related projects (e.g., Peyer et al., 2016) is that learners partially reach the standards, with substantial differences between languages and skills. However, much less is known in regards to specific linguistic competences. Therefore, the major motivation of SWIKO is to empirically document and analyze learners’ interlanguage – in view of the aforementioned paradigm shift and in particular in regards to lexis and grammar – at the end of mandatory schooling.

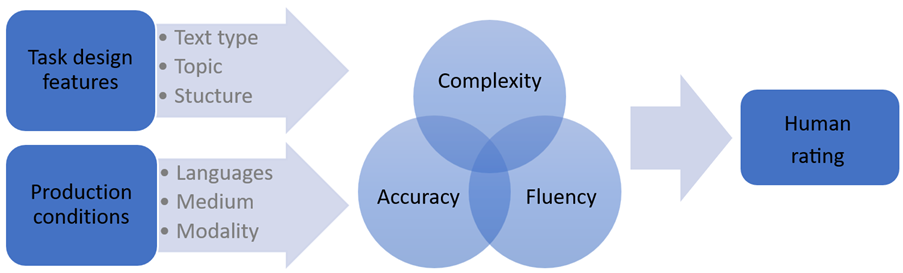

In line with the realm of the action-oriented classroom, students’ productions in the SWIKO corpus are task based. Particular attention is devoted to the interplay of various conditions of the productions – the language (German, French, and Englisch, both as the language of schooling (LoS) and foreign language (FL)), modality (written vs. oral production), medium (computer vs. paper-based) – and task design features, i.e., the text type (descriptive vs. argumentative), topic familiarity (academic vs. leisure), and structure (more or less restrictive input), in order to address the question of how changes in these variables influence the quality of a learner production.

Our trilingual parallel corpus complements a wealth of existing ones in that it targets the public school context, low-level learners, and several languages as both the language of schooling as well as foreign languages.

Current scope

As of February 2024, data was collected from three different curriculum regions, recorded in the following sub-corpora:

- SWIKO17 (French-speaking Switzerland, German 1st FL, English 2nd FL)

- SWIKO18 (German-speaking Switzerland, French 1st FL, English 2nd FL)

- SWIKO19 (German-speaking Switzerland, German and English as LoS)

- SWIKO22 (French-speaking Switzerland, German 1st FL, English 2nd FL).

Participants worked on the tasks in both in their language of schooling (LoS) as well as their foreign languages (FL). This results in a trilingual (German, English, and French) learner corpus.

Data collection and task variation [Back]

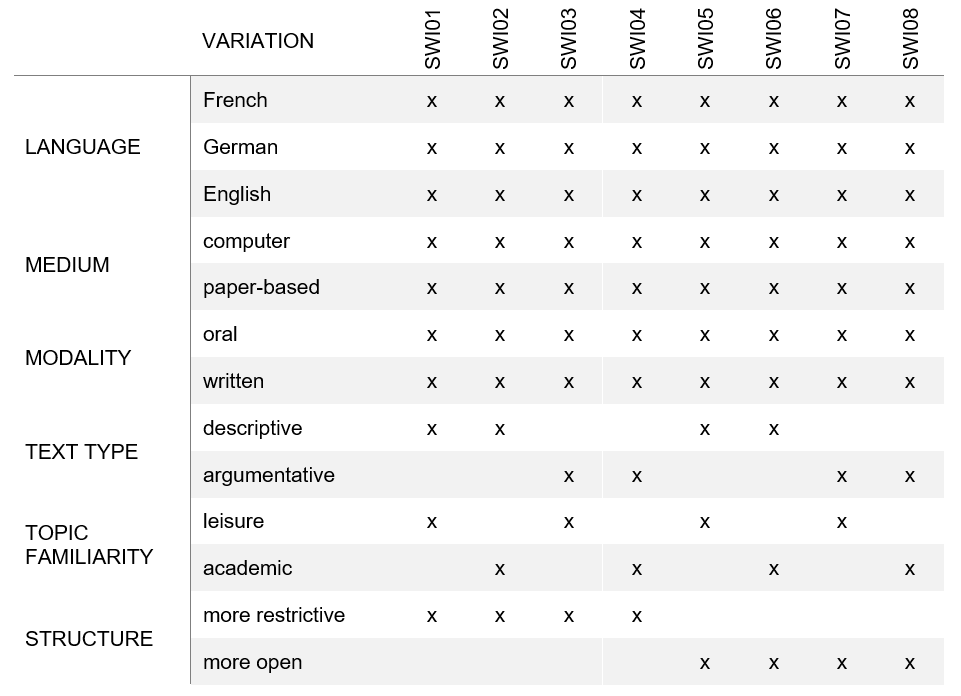

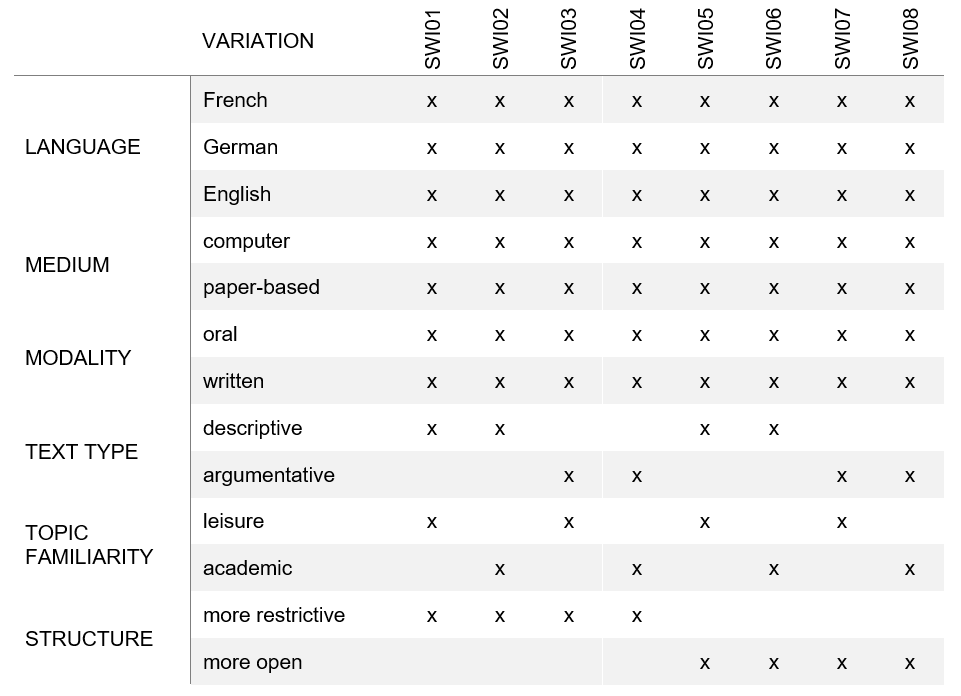

To reflect the scope of tasks in instructed foreign language classes, eight tasks were created and systematically varied along three characteristics: text type, topic familiarity, and structure. Pupils completed the tasks under various conditions: in three languages as both their language of schooling and foreign languages, as well as two types of medium and modality.

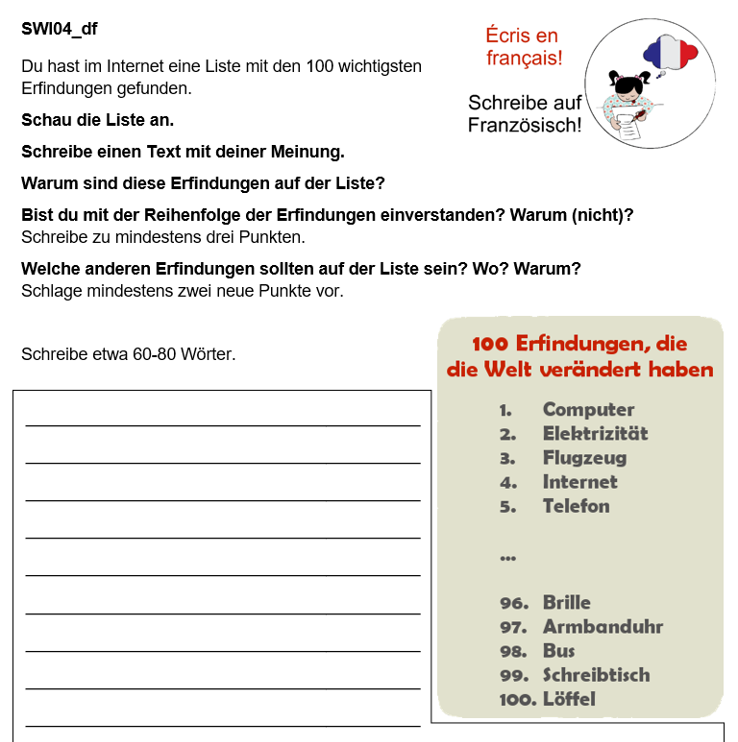

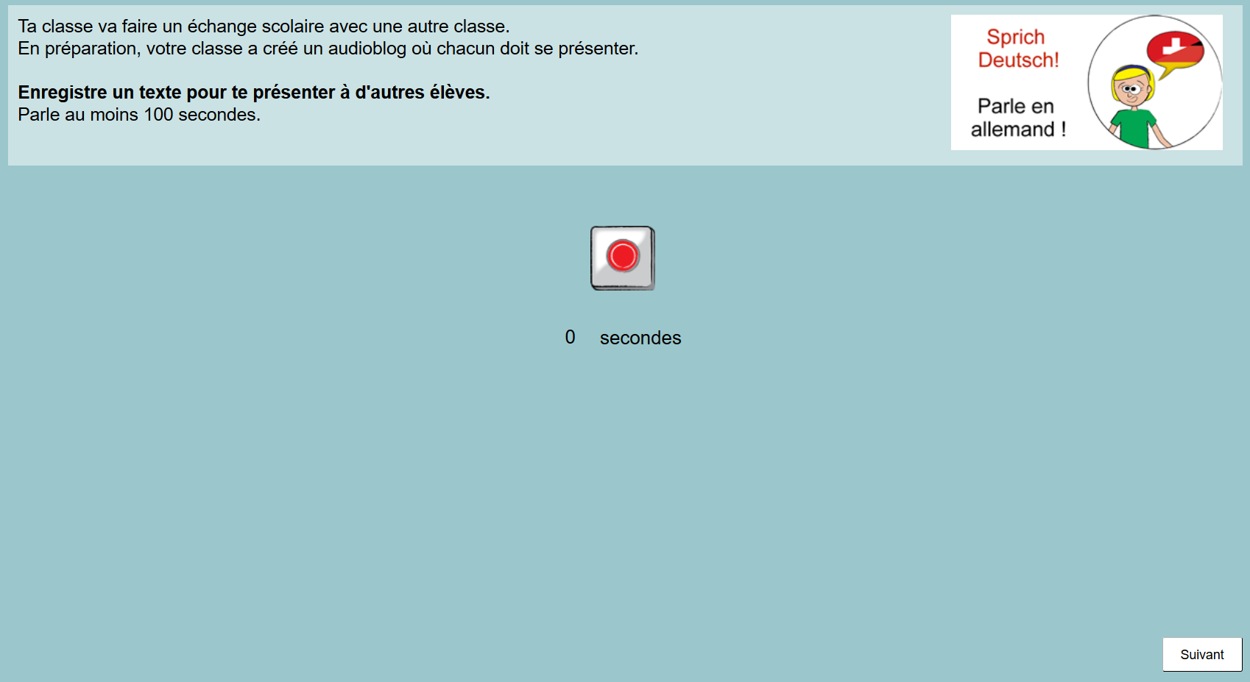

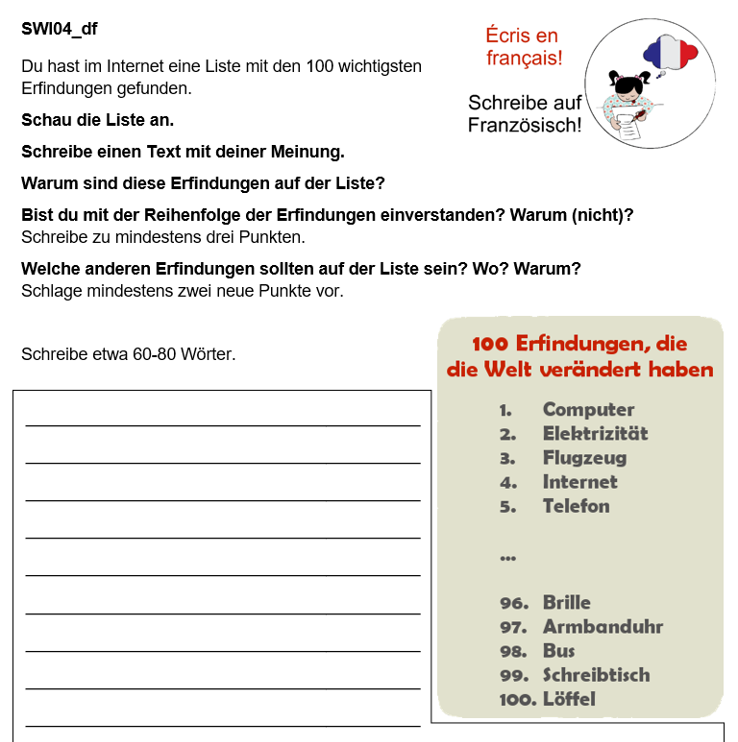

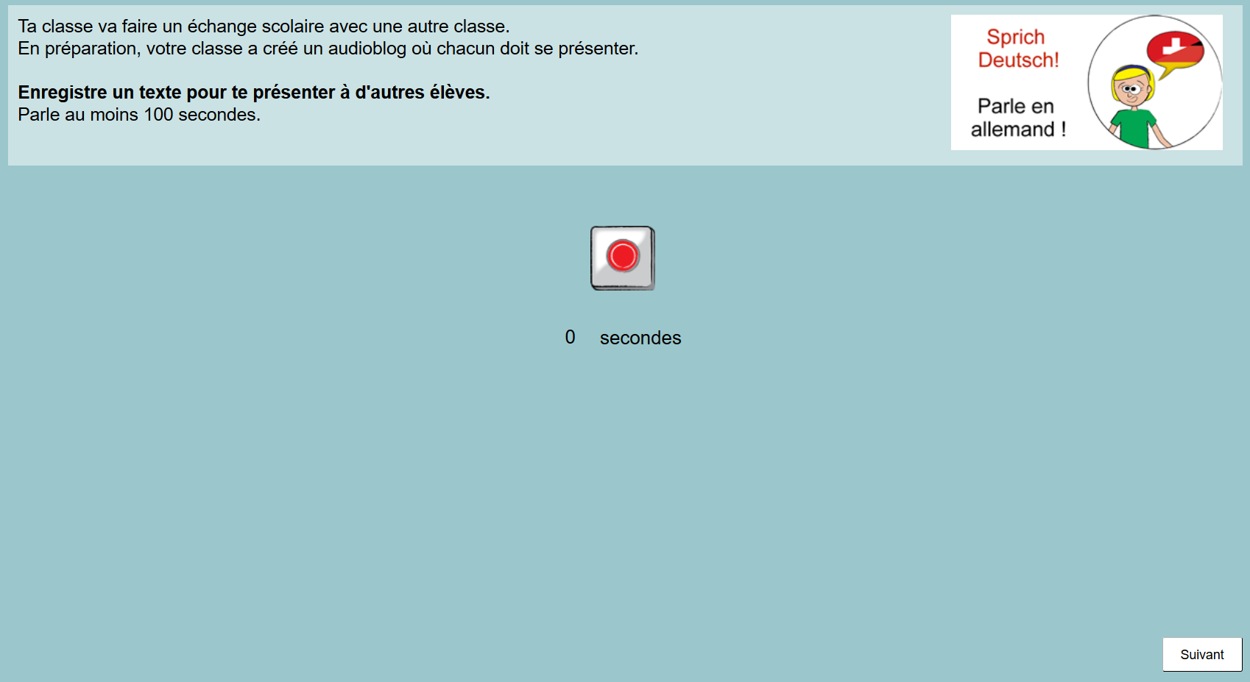

The complementary tasks SWI04 and SWI05 illustrate the variation of task characteristics and production conditions in SWIKO:

In task SWI04, learners had to discuss a list of the top 100 most important inventions. In the example, the task is presented to students with German as the language of schooling, asking to answer in French as their foreign language. This results in a written, paper-based text that is categorized as argumentative, on an academic topic, with a more restricted structure.

In contrast, in task 5, learners were asked to create a self-portrait for a class exchange. Here the task is presented to students with French as the language of schooling asking for a spoken, computer-based answer in German as their foreign language. The task is categorized as descriptive, on a personal topic, with less structure.

Data was collected between 2017-2022 from 14-17 year old students in Grades 10-12 in three Swiss regions: nine classes in French-speaking Switzerland with German as a first and English as a second foreign language; six German-speaking Switzerland with French as a first and English as a second foreign language; and one class German-speaking Switzerland with both English and German as the language of instruction. Students worked on the tasks for 2x45min during regular school hours.

Task variation

The eight tasks were roughly based on the TBLT framework (task-based language teaching, e.g., Ellis et al. 2020, Long, 2015), and varied along three characteristics:

- texttype (or rhetorical mode in Ellis et al. 2020, or linguistic macrofunction in the CEFR, 2001, or text genre in CIIP, 2010), characterized as either descriptive or argumentative;

- topic familiarity (BLC and HLC, Hulstijn, 2015), characterized as either personal or academic;

- structure (Samuda & Bygate, 2008), characterized as either personal or academic

Systematically varying these three characteristics led to a different combination for each of the 8 tasks. The prompts were as follows:

- SWI01: Answer short personal questions

- SWI02: Describe graphs about pets in Switzerland

- SWI03: Discuss a list of vacation options

- SWI04: Discuss a list of the most important inventions

- SWI05: Create a self-portrait for a class exchange

- SWI06: Present a topic (out of 8 options provided)

- SWI07: Discuss whether school should start and end at a later time

- SWI08: Discuss whether foreign language classes should be replaced with a language exchange abroad

Production conditions: Language, medium and modality

Additionally, the productions were completed under three conditions:

- three languages (German, English, and French), as both the language of schooling (L1 for most students) and foreign langauges, respectively, depending on the location of the data collection; each participant completed completed four tasks each in two of their three languages

- written and spoken mode

- computer- and paper-based (medium)

All tasks were developed both as a computer-based version with the software CBA Item Builder (DIPF & Nagarro, 2018b), and as an identical, paper-based (i.e., not-computerised) version. The instructions were always given in the language of schooling to avoid misunderstandings (Barras et al., 2016; Karges et al., 2021). The written formats offered an answer field with a number indicating how many words students were expected to write, whereas in the spoken, computer-based format, students controlled their recording by clicking a red button and were instructed to speak for at least 100 seconds, though most of them ended up shorter.

Data processing [Back]

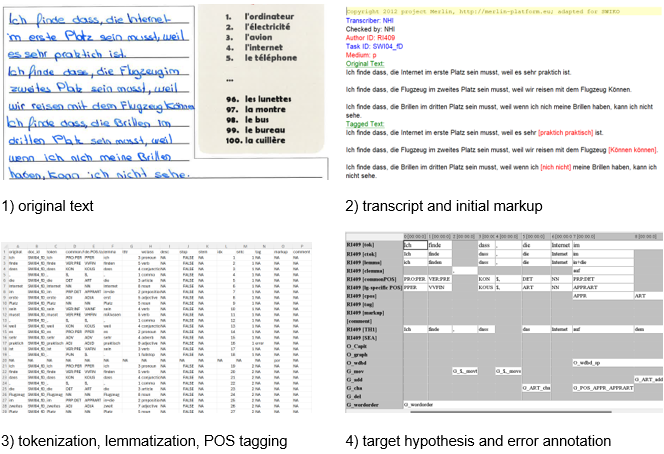

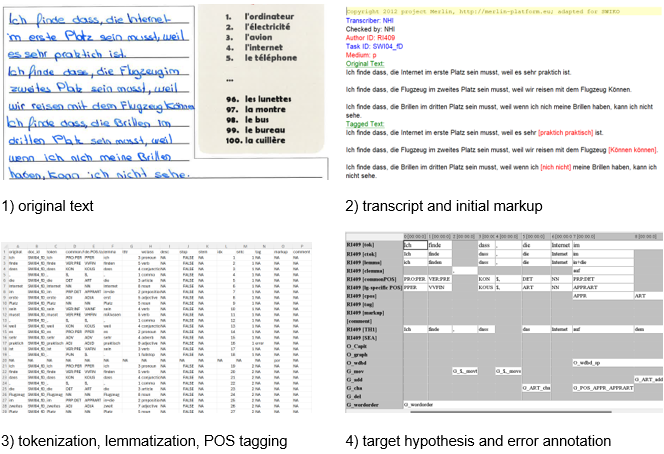

Following data collection, the original learner texts were transcribed as close to the original as possible, and annotated manually to prepare for the POS tagging. Then, they were tokenized, lemmatized, and POS annotated using TreeTagger, both with language-specific tags from the koRpus package, as well as common POS tags that we created to enable comparisons of all texts across all three languages. Finally, they were imported to EXMARaLDA, and all written German productions additionally enhanced with a target hypothesis and semi-automated error annotation.

In a next step, all written productions were rated by trained raters based on four linguistic criteria: vocabulary, grammar, spelling, and text using CEFR descriptors. The ratings were then analyzed using a Many-facet Rasch analysis to ensure fair and consistent evaluation. An example for written texts is given below.

Transcription and initial markup

All productions were transcribed twice: Once as close to the original as possible, and once including markups to prepare for the automatic annotation in the following step. For example, spelling mistakes were corrected and non-target words translated, while always recording both the original and corrected forms. The transcription and annotation guidelines are based on an XML-script, which was kindly made available by the MERLIN project team. Written productions were transcribed in XMLmind (Shafie, 2021). For the oral data, the EXMaRALDA Partitut-Editor (Schmidt & Wörner, 2009) was used, and the guideline was developed based on a comparison of several transcription systems (e.g., GAT2: Selting et al. 2009).

Download the transcription guidelines for written prdoductions

Download the transcription guidelines for oral prdoductions

Download the guidelines for initial error markup

Annotation

In the next step, the transcriptions were transformed to csv ./homepages using specifically developed R scripts (R Core Team, 2022) and were tokenized, lemmatized and POS-tagged using TreeTagger (Schmid, 2013) and the koRpus package (Michalke, 2019). We included both the language-specific POS tags (e.g., STTS for German) and determined a common POS-tag across all three languages. For all written German texts, a target hypothesis – an orthographically and grammatically correct version (Lüdeling & Hirschmann, 2015) – was defined for each learner text, which formed the basis for a semi-automated error annotation. Furthermore, all oral German texts were error-annotated manually.

Download the guidelines for the target hypothesis

Download an explanation of the error annotation with examples

Rating

All foreign language learner texts were rated along the levels Pre-A1 to B2+ using descriptors from lingualevel (Lenz & Studer, 2008) and the Common European Framework of Reference companion volume (Council of Europe, 2020). The raters had to complete two training modules and used the following rating grid to assess the productions along the four analytic criteria vocabulary, grammar, spelling, and text.

Download the rating grid

We then conducted a Many-facet Rasch analysis (Eckes, 2015; Linacre, 1994) using FACETS (Linacre, 2022) using a 3-facet analysis (texts x raters x 4 criteria) per language to obtain a fair score for each production. In German, four raters (R09, R18, R20 and R22) were continuously excluded due to unsatisfactory in- and outfit measures. A comparison of rater severity across the languages further revealed that the German raters were less strict overall; thus, the fair scores of all German texts were lowered by -0,05 (for example, from 5,19 to 5,13).

Download the MFRM-output for German as a foreign language

Download the MFRM-output for English as a foreign language

Download the MFRM-output for French as a foreign language

Publications [Back]

Articles and book chapters

Hicks, N. S. & Studer, T. (2024). Language corpus research meets foreign language education: examples from the multilingual SWIKO corpus. Babylonia Multilingual Journal of Language Education, 2,26-35

Download Arbeitsblätter Negation im DaF-Unterricht

Studer, T. & Hicks, N. S. (i.V.). Zugang zu und Umgang mit fremdsprachlichen Lernertexten unter den Vorzeichen schulisch intendierter Mehrsprachigkeit: Befunde und Herausforderungen am Beispiel des Schweizer Lernerkorpus SWIKO. Book chapter in Schmelter, L. (ed.).

Karges, K., Studer, T., & Hicks, N. S. (2022). Lernersprache, Aufgabe und Modalität: Beobachtungen zu Texten aus dem Schweizer Lernerkorpus SWIKO. Zeitschrift für germanistische Linguistik, 50(1), 104–130.

Karges, K., Studer, T., & Wiedenkeller, E. (2020). Textmerkmale als Indikatoren von Schreibkompetenz. Bulletin suisse de linguistique appliquée, No spécial Printemps 2020, 117–140.

Karges, K., Studer, T., & Wiedenkeller, E. (2019). On the way to a new multilingual learner corpus of foreign language learning in school: Observations about task variation. In A. Abel, A. Glaznieks, V. Lyding, & L. Nicolas (Hrsg.), Widening the Scope of Learner Corpus Research. Selected papers from the fourth Learner Corpus Research Conference (pp. 137–165). Presses universitaires de Louvain.

Talks

Studer, T. & Hicks, N. S. (2024). Korpora konkret: Nutzung eines mehrsprachige Lernerkorpus im schulischen DaF-Unterricht [presentation]. RPFLC, Fribourg.

Hicks, N. S. & Studer, T. (2024). «Da muss einfach mehr Fleisch an den Knochen» - Ein Gespräch über den Nutzen des Lernerkorpus SWIKO für den Fremdsprachenunterricht [Interview]. CEDILE.

Hicks, N. S. (2023). Lexical features in adolescents’ writing: Insights from the trilingual parallel corpus SWIKO [presentation]. Workshop on Profiling second language vocabulary and grammar, University of Gothenburg.

Liste Lamas, E., Runte, M, & Hicks, N. S. (2023). Datenbasiertes Lehren und Lernen mit Korpora im Fremdsprachenunterricht [workshop]. Internationale Delegiertenkonferenz IDK, Winterthur.

Studer, T. & Hicks, N. S. (2022). The interplay of task variables, linguistic measures, and human ratings: Insights from the multilingual learner corpus SWIKO [presentation]. European Second Language Acquisition Conference, Fribourg.

Weiss, Z., Hicks, N. S., Meurers, D., & Studer, T. (2022). Using linguistic complexity to probe into genre differences? Insights from the multilingual SWIKO learner corpus [presentation]. Learner Corpus Research Conference, Padua.

Studer, T., Karges, K., & Wiedenkeller, E. (2019). Machen Tasks den Unterschied? Ein korpuslinguistischer Zugang zur Qualität von Lernertexten in den beiden Fremdsprachen der obligatorischen Schule [presentation]. Studientag VALS-ASLA: Mehrschriftlichkeit im Fremdsprachenerwerb, Brugg.

Karges, K., Wiedenkeller, E., & Studer, T. (2018). Task effects in the assessment of productive skills – a corpus-linguistic approach [poster]. 15th EALTA conference, Bochum.

Teaching and material design [Back]

The following article provides an example of how SWIKO can be used to create teaching material for German as a foreign language classes at lower secondary school levels based on the case of negation in German.

Hicks, N. S. & Studer, T. (2024). Language corpus research meets foreign language education: examples from the multilingual SWIKO corpus. Babylonia Multilingual Journal of Language Education, 2,26-35

Download Arbeitsblätter Negation im DaF-Unterricht

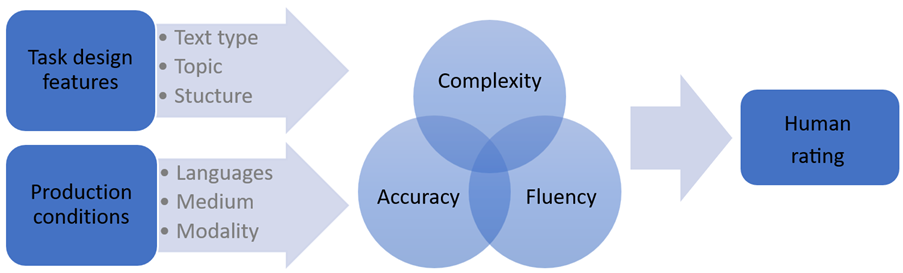

Based on Granger’s (2015) Contrastive Interlanguage Analysis, the SWIKO corpus allows for a wide variety of interesting research enquiries considering

- Task design features (text type, topic familiarity, structure) and production conditions (languages, modus, modality)

- Linguistic properties of the resulting productions (e.g., based on the CAF framework by Bulté et al. 2012: complexity, accuracy, fluency)

- CEFR ratings

Examples can be found in the publication section.