Le corpus suisse des apprenant-e-s SWIKO

Le corpus suisse des apprenant-e-s SWIKO fait partie des projets de recherche SWIKO et WETLAND de l'Institut de plurilinguisme à Fribourg (CH). Actuellement, le corpus comprend plus de 2600 textes annotés contenant plus de 170 000 tokens. Ils sont basés sur des productions orales et écrites d’élèves suisses du secondaire I en allemand, en français et en anglais, à la fois comme langue de scolarisation et langue étrangère.

Ce site web fournit des informations sur le projet, notamment en ce qui concerne la collecte et le traitement des données, à partir d’un certain nombre de documents internes au projet. En outre, nous proposons des cas d’application en classe, la conception de matériaux et la recherche.

La banque de données de corpus en ligne est actuellement accessible via un login personnalisé qui peut être obtenu directemment via SWIKOweb.

Conception du corpus

Scénarios d’utilisation

Contexte et objectifs

SWIKO est un corpus parallèle multilingue, développé au cours de deux phases de projet de recherche au Centre scientifique de compétence sur le plurilinguisme à Fribourg, Suisse. Le projet étudie certains domaines de compétences linguistiques des jeunes apprenant une langue à l’école secondaire (secondaire I) en Suisse. L’idée du projet est née d’un changement dans l’enseignement des langues étrangères : au tournant du XXIe siècle, les priorités de l’enseignement se sont orientées sur les compétences, l’action, le contenu et les tâches (Conseil de l’Europe, 2001). En Suisse, cette évolution a coïncidé avec le projet HarmoS, qui a unifié l’enseignement des langues étrangères dans les écoles publiques de la plupart des cantons (par exemple, Plan d’études romand (PER), CIIP, 2024 ; ou New World, Arnet-Clark et al., 2013). Ainsi, deux langues étrangères sont devenues obligatoires à l’école primaire : la première à partir de la 5e HarmoS, la seconde à partir de la 7e HarmoS, avec une langue nationale plus l’anglais. Par exemple, en Suisse romande, les élèves commencent à apprendre l’allemand à l’âge de 8 ans et l’anglais à l’âge de 10 ans. À la fin de la scolarité obligatoire – en 11e année HarmoS, à l’âge de 15 ans – les élèves sont censé-e-s atteindre le niveau A2.2 en général et le niveau A2.1 à l’écrit. Ces niveaux s’appliquent aux deux langues étrangères.

Ce que nous savons jusqu’à présent grâce à un premier suivi national (COFO, 2019) et à des projets connexes (par exemple, Peyer et al., 2016), c’est que les élèves atteignent partiellement les niveaux, avec des différences substantielles entre les langues et les compétences. Cependant, nous en savons beaucoup moins sur les compétences linguistiques spécifiques. Par conséquent, la principale motivation de SWIKO est de documenter et d’analyser empiriquement l’interlangue des élèves – compte tenu du changement de paradigme susmentionné et en particulier en ce qui concerne les compétences lexicales et grammaticales – à la fin de la scolarité obligatoire.

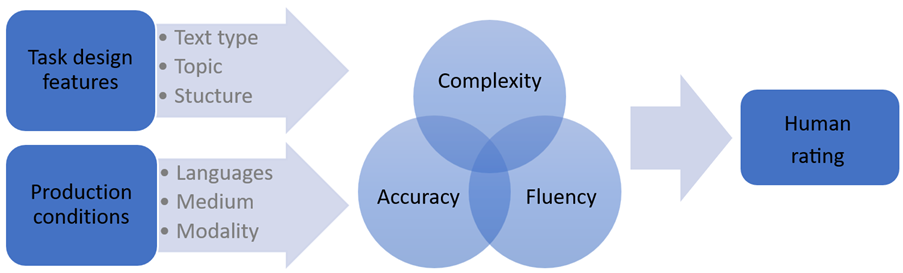

Conformément au principe de l’approche actionnelle, les productions des élèves dans le corpus SWIKO sont basées sur des tâches. Une attention particulière est accordée à l’interaction des différentes conditions de production – la langue (allemand, français et anglais, à la fois comme langue de scolarisation (LdS) et langue étrangère (LE)), la modalité (production écrite ou orale), le support (ordinateur ou papier) – et les caractéristiques de conception de la tâche, c’est-à-dire le type de texte (descriptif ou argumentatif), la familiarité du sujet (académique ou de loisir) et la structure (plus ou moins restrictive), afin de déterminer comment les changements de ces variables influencent la qualité de la production d’un-e apprenant-e.

Notre corpus parallèle trilingue complète une multitude de corpus existants en ce sens qu’il cible le contexte de l’école publique, les élèves de bas niveau et plusieurs langues en tant que langues de scolarisation et langues étrangères.

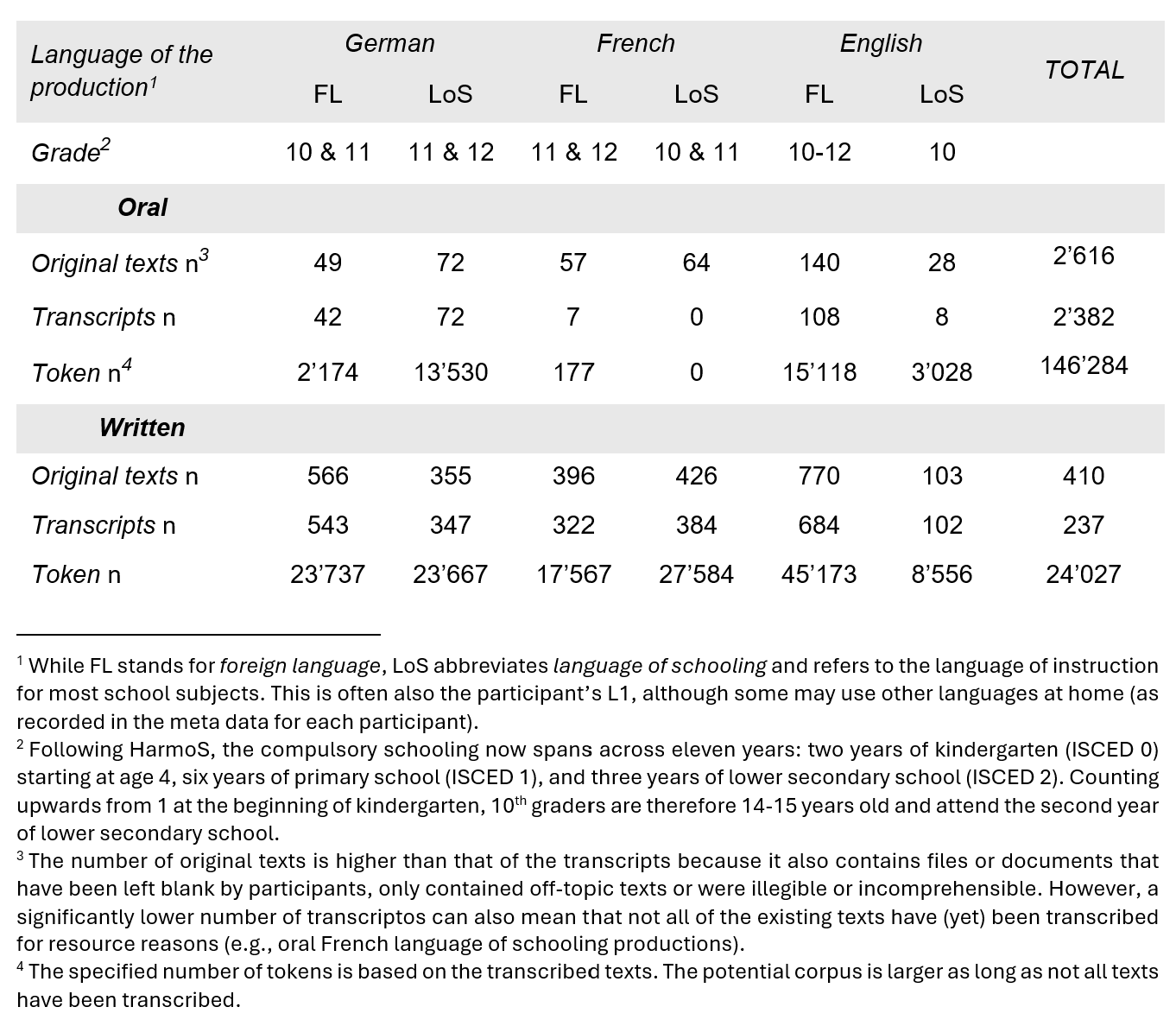

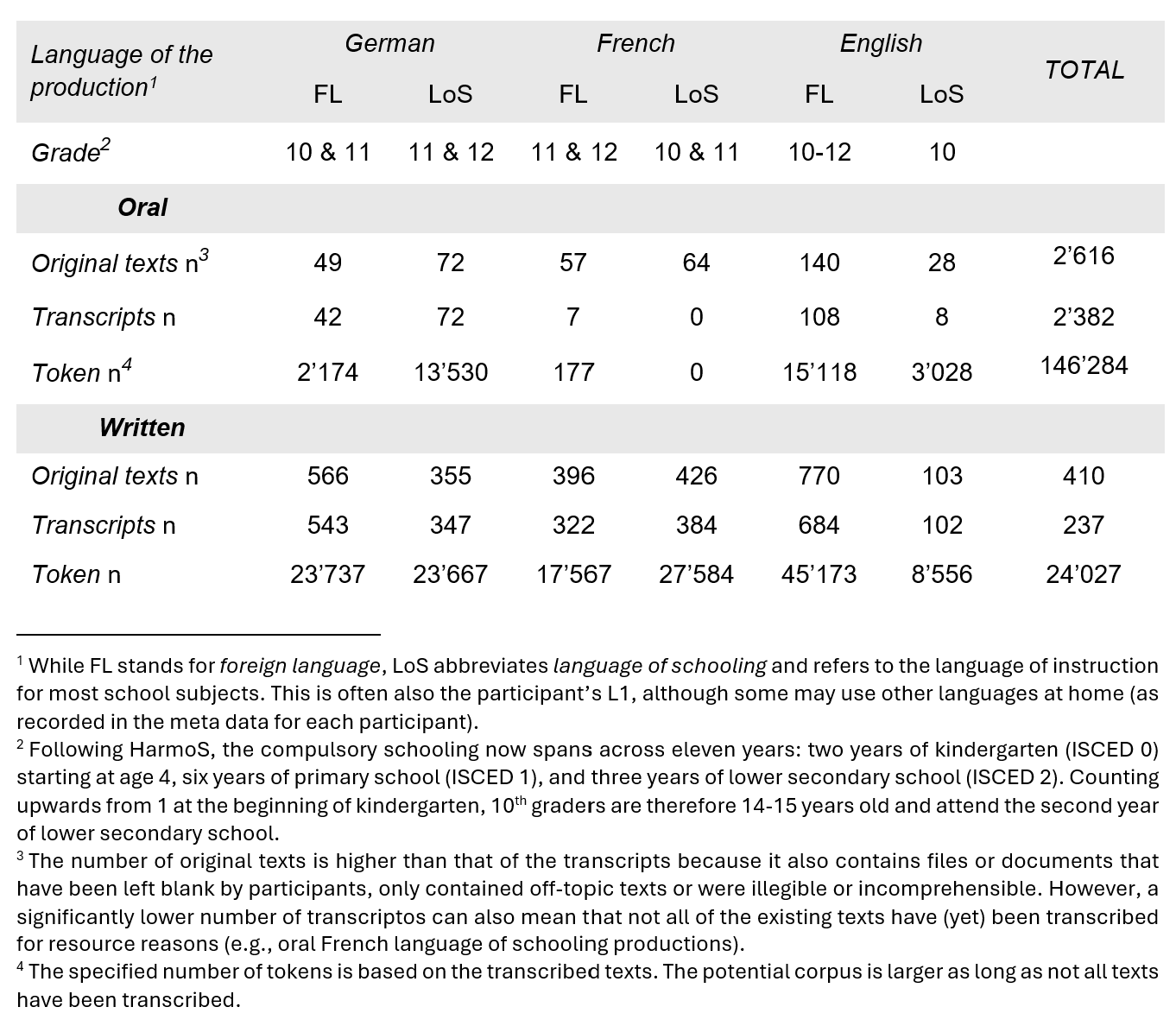

Étendue actuelle

En février 2024, des données ont été collectées dans trois régions au curriculum différent, enregistrées dans les sous-corpora suivant :

- SWIKO17 (Suisse romande, allemand 1re LE, anglais 2e LE)

- SWIKO18 (Suisse alémanique, français 1re LE, anglais 2e LE)

- SWIKO19 (Suisse alémanique, allemand et anglais comme LdS)

- SWIKO22 (Suisse romande, allemand 1re LE, anglais 2e LE).

Les participant-e-s ont travaillé sur des tâches à la fois dans leur langue de scolarisation (LdS) et dans leurs langues étrangères (LE). Il en résulte un corpus d’apprenant-e-s trilingue (allemand, anglais et français).

Collecte de données et variation des tâches [Retour]

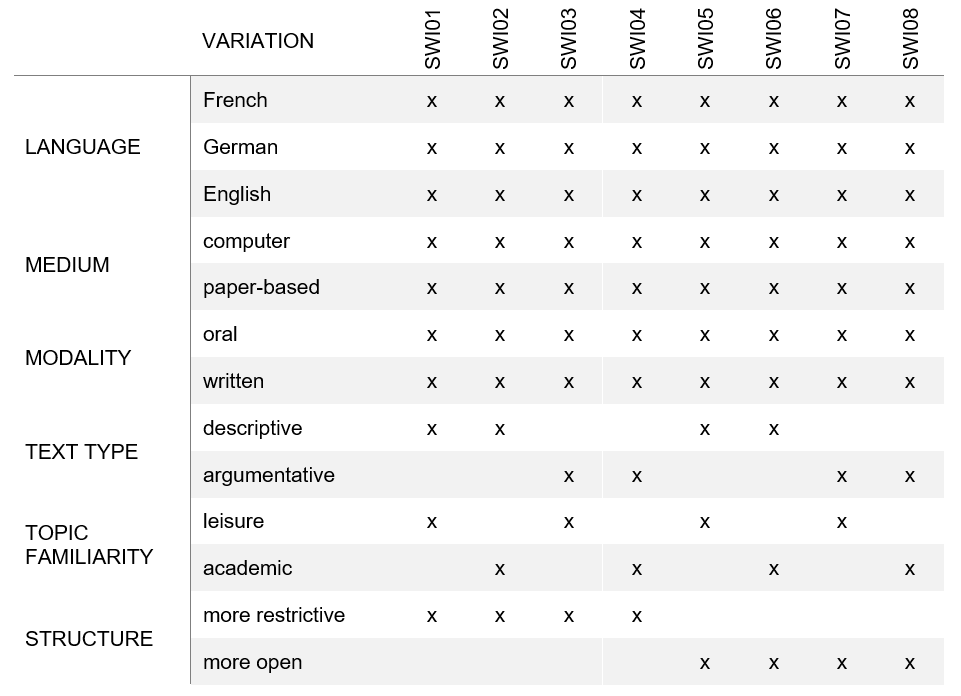

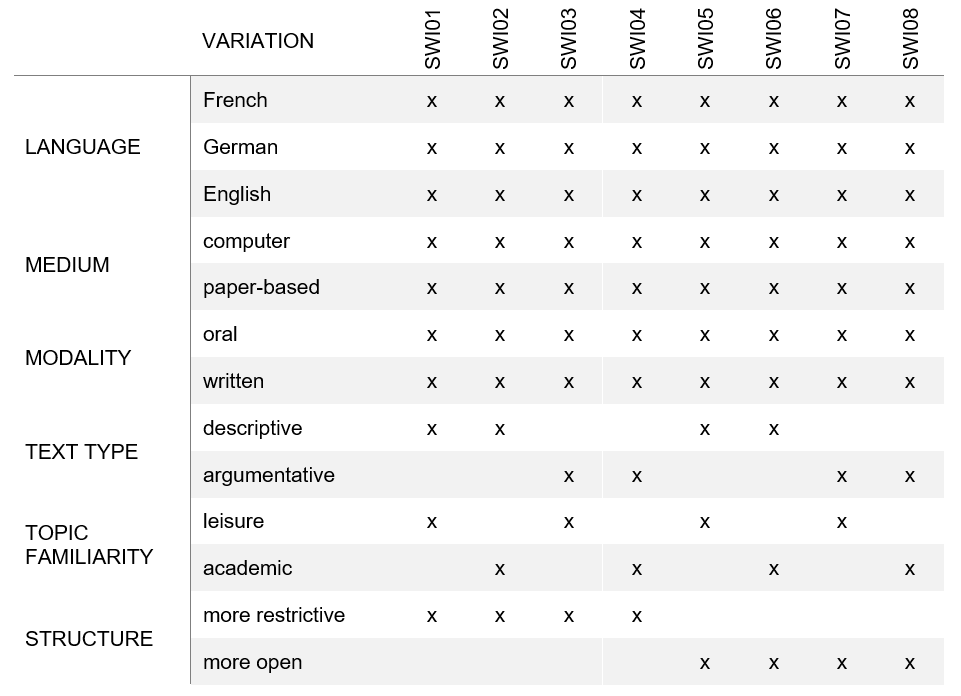

Afin de refléter l’étendue des tâches dans les classes de langues étrangères enseignées, huit tâches ont été créées et systématiquement modifiées en fonction de trois caractéristiques : le type de texte, la familiarité avec le sujet et la structure. Les élèves ont effectué des tâches dans diverses conditions : dans trois langues, c’est-à-dire leur langue de scolarisation et leurs langues étrangères, ainsi que sur deux types de supports et de modalités.

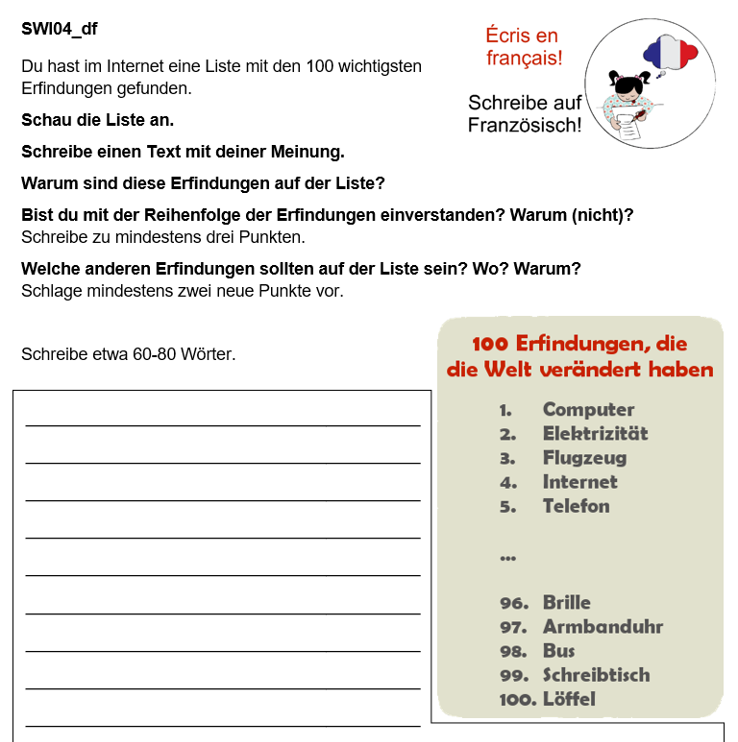

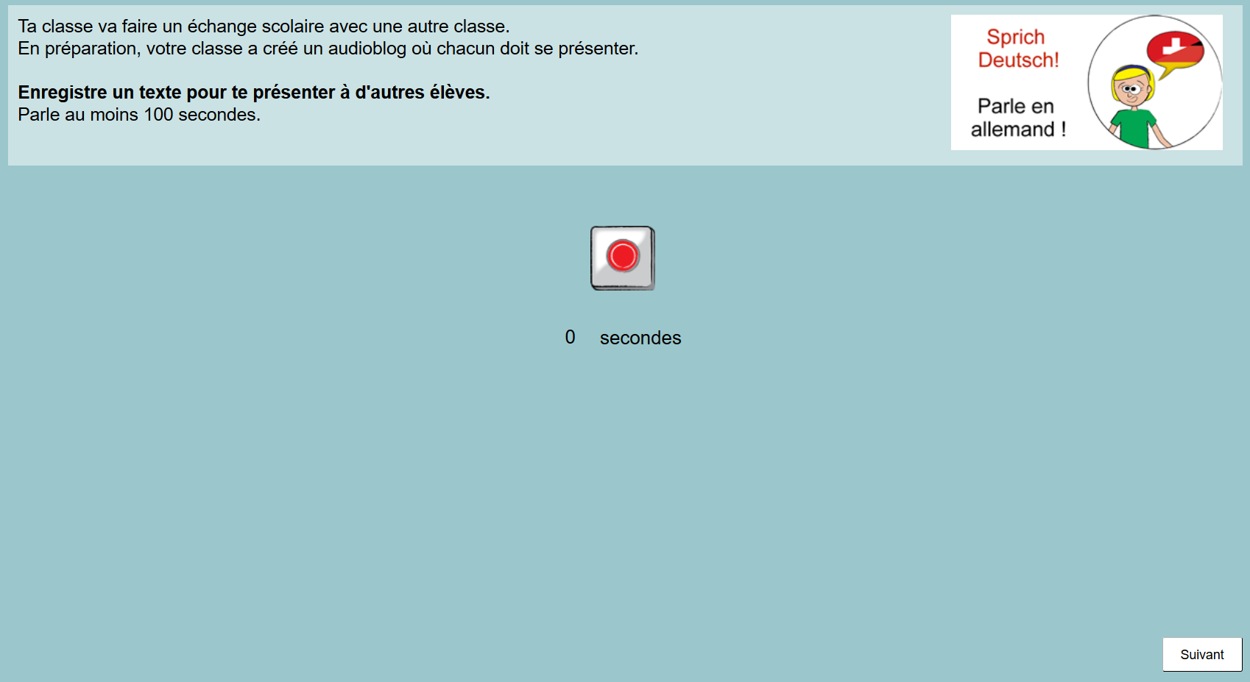

Les tâches complémentaires SWI04 et SWI05 illustrent la variation des caractéristiques des tâches et des conditions de production dans SWIKO :

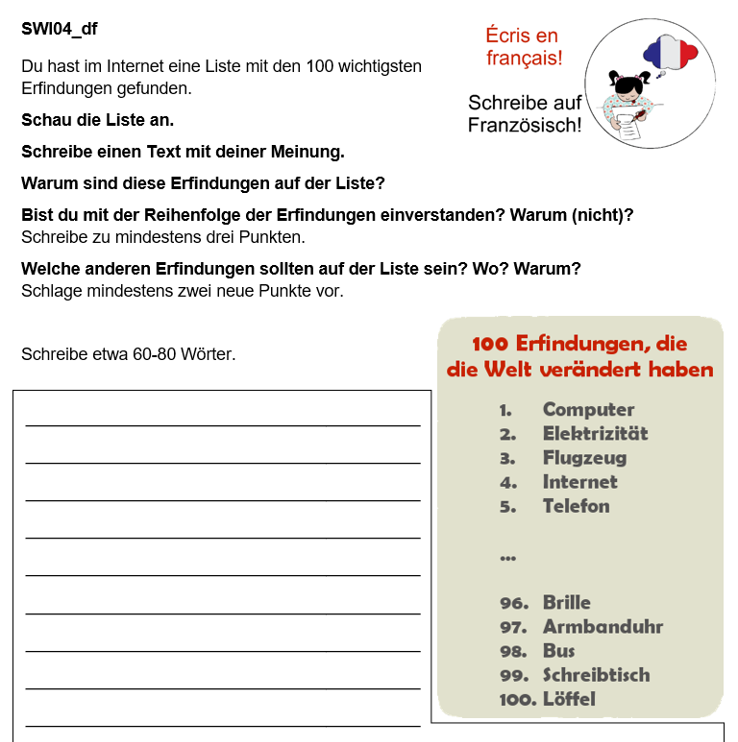

Dans la tâche SWI04, les élèves devaient discuter d’une liste des 100 inventions les plus importantes. Dans l’exemple, la tâche est présentée à des élèves dont l’allemand est la langue de scolarisation et qui doivent répondre en français, leur langue étrangère. Il en résulte un texte écrit, sur papier, catégorisé comme argumentatif, sur un sujet académique, avec une structure assez restreinte.

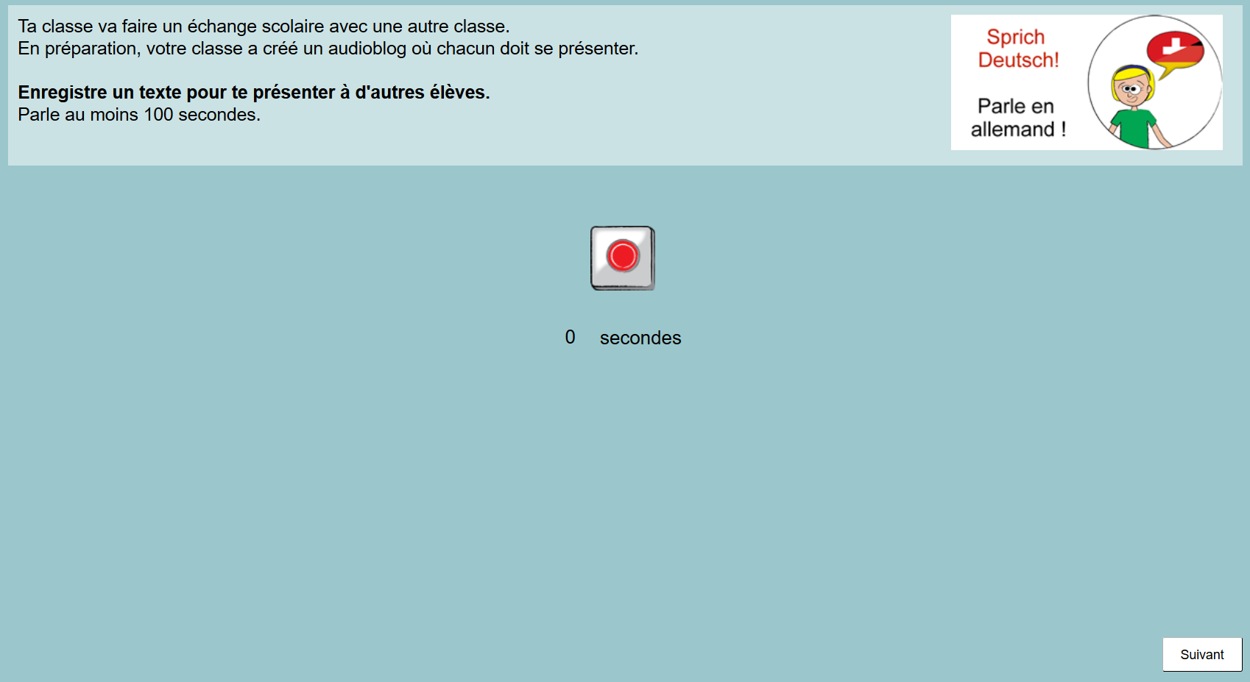

En revanche, dans la tâche 5, les élèves ont été invité-e-s à créer un autoportrait pour une présentation en classe. Ici, la tâche est soumise à des élèves dont le français est la langue de scolarisation et demande une réponse orale, assistée par ordinateur, en allemand, leur langue étrangère. La tâche est classée comme descriptive, sur un sujet personnel, avec moins de structure.

Les données ont été collectées entre 2017-2022 auprès d’élèves de 14 à 17 ans en 10e à 12e année HarmoS, dans trois régions suisses : neuf classes de Suisse romande avec l’allemand comme première et l’anglais comme deuxième langue étrangère ; six classes de Suisse alémanique avec le français comme première et l’anglais comme deuxième langue étrangère ; et une classe de Suisse alémanique avec l’anglais et l’allemand comme langues d’enseignement. Les élèves ont travaillé sur les tâches pendant 2 × 45 minutes pendant les heures de cours normales.

Variation des tâches

Les huit tâches étaient globalement basées sur le cadre TBLT (enseignement des langues basé sur des tâches, par exemple Ellis et al. 2020, Long, 2015) et varient selon trois caractéristiques :

le type de texte (ou mode rhétorique dans Ellis et al. 2020, ou macrofonction linguistique dans le CECR, 2001, ou genre de texte dans CIIP, 2010) différencié entre descriptif et argumentatif ;

la familiarité avec le sujet (BLC et HLC, Hulstijn, 2015), différenciée entre personnelle et académique ;

la structure (Samuda & Bygate, 2008), différenciée entre plus ou moins restrictive.

La variation systématique de ces trois caractéristiques a permis d’obtenir une combinaison différente pour chacune des huit tâches. Les tâches étaient les suivantes :

SWI01: Répondre à de courtes questions personnelles

SWI02: Commenter des graphiques concernant les animaux de compagnie en Suisse

SWI03: Discuter d’une liste d’idées de vacances

SWI04: Discuter d’une liste des inventions les plus importantes

SWI05: Créer son autoportrait pour une présentation en classe

SWI06: Présenter un sujet (parmi les 8 options proposées)

SWI07: Discuter de l’opportunité de commencer et de terminer l’école à une heure plus tardive

SWI08: Discuter de l’opportunité de remplacer les cours de langues étrangères par un échange linguistique à l’étranger.

Conditions de production : langue, support et modalité

DEn outre, les productions ont été réalisées dans trois conditions :

trois langues (allemand, anglais et français), à la fois comme langue de scolarisation (L1 pour la plupart des élèves) et comme langues étrangères, respectivement, en fonction du lieu de collecte des données ; chaque participant-e a effectué quatre tâches dans deux des trois langues ;

mode écrit et oral ;

sur ordinateur et sur papier (support).

Toutes les tâches ont été développées sous la forme d’une version informatisée avec le logiciel CBA Item Builder (DIPF & Nagarro, 2018b) et d’une version identique sur papier (c’est-à-dire non informatisée). Les instructions ont toujours été données dans la langue de scolarisation afin d’éviter les malentendus (Barras et al., 2016 ; Karges et al., 2021). Les formats écrits proposaient un champ de réponse avec un chiffre indiquant le nombre de mots que les élèves devaient écrire, tandis que dans le format oral, assisté par ordinateur, les élèves géraient leur enregistrement en cliquant sur un bouton rouge et avaient pour instruction de s’exprimer pendant au moins 100 secondes, bien que la plupart aient parlé moins longtemps.

Traitement des données [Retour]

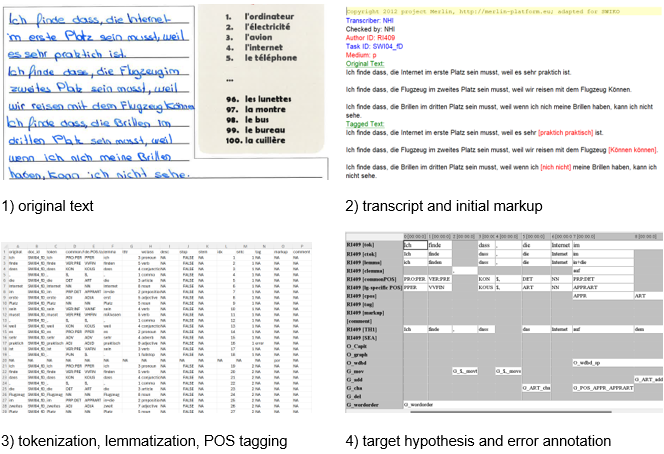

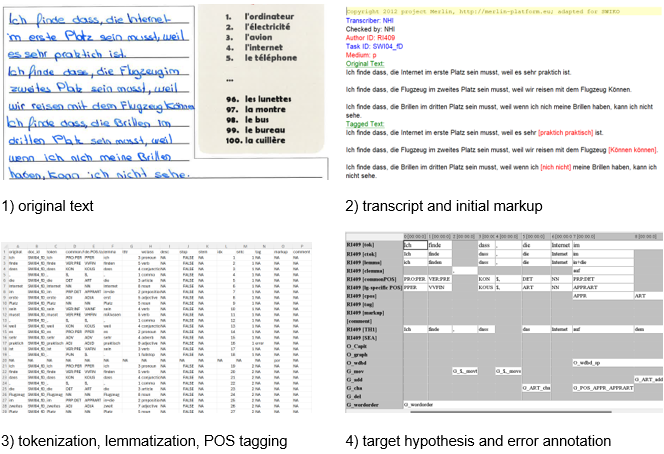

Après la collecte des données, les textes originaux des élèves ont été transcrits au plus près de l’original et annotés manuellement pour préparer l’étiquetage grammatical (le tagging POS – part-of-speech tagging). Ils ont ensuite été tokenisés, lemmatisés et annotés grammaticalement à l’aide de TreeTagger, à la fois avec des étiquettes spécifiques à la langue provenant du paquet koRpus et avec des étiquettes grammaticales communes que nous avons créées pour permettre des comparaisons de tous les textes dans les trois langues. Enfin, ils ont été importés dans EXMARaLDA, et toutes les productions écrites en allemand ont été enrichies d’une hypothèse cible et d’une annotation semi-automatique des erreurs.

À l’étape suivante, des personnes formées ont noté toutes les productions écrites sur la base de quatre critères linguistiques : le vocabulaire, la grammaire, l’orthographe et la rédaction, en utilisant les descripteurs du CECR. Les notes ont ensuite été évaluées à l’aide d’une analyse Rasch multifacette afin de garantir une évaluation juste et cohérente. Un exemple de texte écrit se trouve ci-dessous.

Transcription et marquage initial

Toutes les productions ont été transcrites deux fois : une fois aussi proche que possible de l’original et une fois en incluant des marques pour préparer l’annotation automatique à l’étape suivante. Les fautes d’orthographe, notamment, ont été corrigées et les mots non ciblés ont été traduits, tout en enregistrant toujours la forme originale et la forme corrigée. Les consignes de transcription et d’annotation sont basées sur un script XML gracieusement mis à disposition par l’équipe du projet MERLIN. Les productions écrites ont été transcrites en XMLmind (Shafie, 2021). L’EXMaRALDA Partitur Editor (Schmidt & Wörner, 2009) a été utilisé pour les données vocales, et la consigne a été élaborée sur la base d’une comparaison de plusieurs systèmes de transcription (par exemple GAT2 : Selting et al. 2009).

Download consignes de transcription pour productions écrites

Download consignes de transcription pour productions orales

Download consignes de marquage initial

Annotation d'erreur

Dans l’étape suivante, les transcriptions ont été transformées en csv à l’aide de scripts R développés spécialement à cet effet (R Core Team, 2022) et ont été tokenisées, lemmatisées et annotés grammaticalement à l’aide de TreeTagger (Schmid, 2013) et du paquet koRpus (Michalke, 2019). Nous avons inclus les étiquettes grammaticales spécifiques à chaque langue (par exemple STTS pour l’allemand) et élaboré une étiquette grammaticale commune aux trois langues. Une hypothèse cible – une version orthographiquement et grammaticalement correcte (Lüdeling & Hirschmann, 2015) – a été définie pour chaque texte d’élève écrit en allemand, et a constitué la base d’une correction semi-automatique des erreurs. En outre, tous les textes oraux en allemand ont été corrigés manuellement.

Download consignes pour hypothèse cible

Download explication de l'annotation d'erreur avec exemples

Rating

Tous les textes d’élèves en langues étrangères ont été évalués selon les niveaux Pré-A1 à B2+ en utilisant les descripteurs lingualevel (Lenz & Studer, 2008) et le volume complémentaire du Cadre européen commun de référence (Conseil de l’Europe, 2020). Les personnes procédant à l’évaluation ont suivi deux modules de formation et utilisé la grille d’évaluation suivante pour évaluer les productions en fonction des quatre critères d’analyse vocabulaire, grammaire, orthographe et structure (cohésion/cohérence).

Download grille d'évaluation

Ensuite, une analyse Rasch multifacette (Eckes, 2015 ; Linacre, 1994) à l’aide de FACETS (Linacre, 2022) a été effectué en utilisant une analyse à 3 facettes (textes × chargé-e-s d’évaluation × 4 critères) par langue afin d’obtenir un score équitable pour chaque production. En allemand, quatre chargé-e-s d’évaluation (R09, R18, R20 et R22) ont été systématiquement exclu-e-s en raison d’indices infit et outfit insatisfaisants. Une comparaison de la sévérité des chargé-e-s d’évaluation entre les langues a également révélé que les chargé-e-s d’évaluation allemands étaient moins stricts dans l’ensemble ; ainsi, les résultats équitables de tous les textes allemands ont été abaissés de -0,05 (par exemple, de 5,19 à 5,14).

Download MFRM-Output allemand langue étrangère

Download MFRM-Output anglais langue étrangère

Download MFRM-Output français langue étrangère

Articles et chapitres de livres

Hicks, N. S. & Studer, T. (2024). Language corpus research meets foreign language education: examples from the multilingual SWIKO corpus. Babylonia Multilingual Journal of Language Education, 2,26-35

Download Arbeitsblätter Negation im DaF-Unterricht

Studer, T. & Hicks, N. S. (i.V.). Zugang zu und Umgang mit fremdsprachlichen Lernertexten unter den Vorzeichen schulisch intendierter Mehrsprachigkeit: Befunde und Herausforderungen am Beispiel des Schweizer Lernerkorpus SWIKO. Book chapter in Schmelter, L. (ed.).

Karges, K., Studer, T., & Hicks, N. S. (2022). Lernersprache, Aufgabe und Modalität: Beobachtungen zu Texten aus dem Schweizer Lernerkorpus SWIKO. Zeitschrift für germanistische Linguistik, 50(1), 104–130.

Karges, K., Studer, T., & Wiedenkeller, E. (2020). Textmerkmale als Indikatoren von Schreibkompetenz. Bulletin suisse de linguistique appliquée, No spécial Printemps 2020, 117–140.

Karges, K., Studer, T., & Wiedenkeller, E. (2019). On the way to a new multilingual learner corpus of foreign language learning in school: Observations about task variation. In A. Abel, A. Glaznieks, V. Lyding, & L. Nicolas (Hrsg.), Widening the Scope of Learner Corpus Research. Selected papers from the fourth Learner Corpus Research Conference (pp. 137–165). Presses universitaires de Louvain.

Présentations

Studer, T. & Hicks, N. S. (2024). Korpora konkret: Nutzung eines mehrsprachige Lernerkorpus im schulischen DaF-Unterricht [presentation]. RPFLC, Fribourg.

Hicks, N. S. & Studer, T. (2024). «Da muss einfach mehr Fleisch an den Knochen» - Ein Gespräch über den Nutzen des Lernerkorpus SWIKO für den Fremdsprachenunterricht [Interview]. CEDILE.

Hicks, N. S. (2023). Lexical features in adolescents’ writing: Insights from the trilingual parallel corpus SWIKO [presentation]. Workshop on Profiling second language vocabulary and grammar, University of Gothenburg.

Liste Lamas, E., Runte, M, & Hicks, N. S. (2023). Datenbasiertes Lehren und Lernen mit Korpora im Fremdsprachenunterricht [workshop]. Internationale Delegiertenkonferenz IDK, Winterthur.

Studer, T. & Hicks, N. S. (2022). The interplay of task variables, linguistic measures, and human ratings: Insights from the multilingual learner corpus SWIKO [presentation]. European Second Language Acquisition Conference, Fribourg.

Weiss, Z., Hicks, N. S., Meurers, D., & Studer, T. (2022). Using linguistic complexity to probe into genre differences? Insights from the multilingual SWIKO learner corpus [presentation]. Learner Corpus Research Conference, Padua.

Studer, T., Karges, K., & Wiedenkeller, E. (2019). Machen Tasks den Unterschied? Ein korpuslinguistischer Zugang zur Qualität von Lernertexten in den beiden Fremdsprachen der obligatorischen Schule [presentation]. Studientag VALS-ASLA: Mehrschriftlichkeit im Fremdsprachenerwerb, Brugg.

Karges, K., Wiedenkeller, E., & Studer, T. (2018). Task effects in the assessment of productive skills – a corpus-linguistic approach [poster]. 15th EALTA conference, Bochum.

Enseignement et conception de matériel [Retour]

L’article suivant donne un exemple de la manière dont SWIKO peut être utilisé pour créer du matériel pédagogique pour les cours d’allemand langue étrangère au niveau secondaire I, en se basant sur le cas de la négation en allemand.

Hicks, N. S. & Studer, T. (2024). Language corpus research meets foreign language education: examples from the multilingual SWIKO corpus. Babylonia Multilingual Journal of Language Education, 2,26-35

Download Arbeitsblätter Negation im DaF-Unterricht

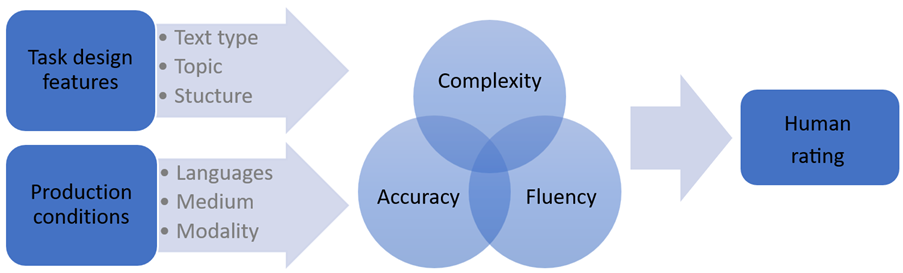

Basé sur l’analyse contrastive interlangue de Granger (2015), le corpus SWIKO offre une grande diversité de recherches intéressantes tenant compte

des caractéristiques de la conception de la tâche (type de texte, familiarité avec le sujet, structure) et des conditions de production (langues, modus, modalité);

des propriétés linguistiques des productions résultantes (par exemple sur la base du cadre CAF de Bulté et al. 2012: complexity, accuracy, fluency);

Notations CECR

Des exemples peuvent être trouvés dans la section publications.